Indications for Use of Non-invasive Transcutaneous Pacing

Indications for NTP as outlined in the AHA’s Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) Provider Manual follow:1

- Hemodynamically unstable bradycardia (e.g. blood pressure changes, acute altered mental status, ongoing severe ischemic chest pain, congestive heart failure, hypotension, syncope or other signs of shock) that persists despite adequate airway and breathing.

- Unstable clinical condition that is likely due to the bradycardia.

- For pacing readiness (i.e. standby mode) in the setting of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) with the following:

- Symptomatic sinus bradycardia

- Mobitz type II second-degree AV block

- Third-degree AV block

- New left, right or alternating bundle branch block or bifascicular block

- Bradycardia with symptomatic ventricular escape rhythms.

- Overdrive pacing of tachycardias refractory to drug therapy or electrical cardioversion.

Transcutaneous pacing should be initiated without delay when there is impairment in the conduction system resulting in a high-degree block (e.g., Mobitz type II second-degree block or third-degree AV block). NTP is considered a Class I intervention for symptomatic bradycardias by the AHA, which means that the risk is much greater than the benefit and the “procedure/treatment or diagnostic test/assessment should be performed/administered.”2 While waiting for the pacemaker device, atropine should be considered. In an emergency, if there is no intravenous access, the atropine is not effective or the patient is severely symptomatic, NTP should be begun immediately by the trained nurse or physician.

NTP can be set up ready to use in patients who are clinically stable yet may quickly decompensate. Patients who may benefit from standby pacing include those:

- With AMI showing signs of early heart block

- Awaiting cardiac surgery

- Awaiting placement of a permanent pacemaker, generator change or lead wire replacement

- Undergoing cardiac catheterization or angioplasty

- At risk of developing post cardioversion bradycardia.3

Bradycardia with escape rhythms is another arrhythmia when TCP may be used. Pulseless electrical

activity (PEA) from drug overdoses, toxic exposure, and electrolyte abnormalities may benefit from the support of NTP while treating the cause.

Overdrive pacing is rarely performed with the standard noninvasive transcutaneous pacemaker. The intent is to pace at a rate faster than the tachycardia in order to interrupt the re-entry circuit so the SA node can regain control of the heart rhythm. The upper rate limit of most devices is < 180 beats/minute, so that they can only be used for slower tachycardias. Rapid ventricular pacing in patients with supraventricular tachycardias may precipitate ventricular fibrillation, and burst ventricular pacing may cause acceleration of ventricular tachycardia. So the procedure should only be performed in the electrophysiology lab by experienced providers.4 Often electrophysiologists are more comfortable performing overdrive pacing using a small generator attached to a transvenous wire they quickly slip in place or the transthoracic wires that were placed on the exterior surface of the heart during cardiac surgery. It is preferable to use a device that can perform programmed stimulation with synchronized extrastimuli, a technique that is least likely to cause detrimental arrhythmias.

Transcutaneous pacing may be utilized when transvenous pacing is contraindicated under the following circumstances:

- Difficulty placing a wire, e.g., tricuspid valve prosthesis

- Potential for bleeding, e.g., patients who have received a thrombolytic

- Increased potential for infection, e.g., patients with depressed immune system.

Since the bradycardia seen frequently in children is usually secondary to hypoxic events, the treatment of choice is prompt airway support, ventilation, and oxygenation. Although less frequently than adults, children and infants do experience heart blocks and bradycardias where treatment with NTP is indicated and could be lifesaving. Indications for use of NTP in children include:

- Bradycardias from surgically acquired AV blocks

- Congenital AV blocks

- Viral myocarditis

- Heart block secondary to toxin or drug overdose

- Permanent pacemaker generator failure.

In the 2010 AHA Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care, the use of pacing for patients with asystolic cardiac arrest is not recommended since randomized controlled trials have failed to show its benefit.5 This absence of P waves and QRS complexes is seen late in arrest when ventricular fibrillation has deteriorated to asystole. Lack of response to pacing is not a failure of the technique of pacing, but rather failure of the hypoxic human heart to respond to pacing with mechanical contractions, despite electrical activity. In the hospital, asystole often represents the final rhythm of a patient whose organs have failed and whose condition has deteriorated. An electrical stimulus in this circumstance usually produces no cardiac response at all, or at the very least, brief episodes of clinically useless PEA.

There are several circumstances in the hospital when asystole appears suddenly and providers are close by to initiate lifesaving pacing:

- When the asystole is the result of a primary conduction system problem and ventricular standstill is noted quickly on the monitor in a critical care unit (P waves may still be present)

- When standstill is drug-induced, e.g., due to procainamide, quinidine, digitalis, beta blockers, verapamil

- With unexpected circulatory arrest, e.g., due to anesthesia, surgery, angiography, and other therapeutic or diagnostic procedures

- With reflex vagal standstill

- When asystole results following defibrillation.

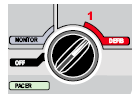

In this last circumstance, it is quick and easy to switch modes on the bedside monitor/defibrillator/pacemaker from defibrillator to noninvasive pacemaker.

Contraindications to NTP include:

- Severe hypothermia since the heart is unable to respond to the electrical stimulus.

- Confused patients since there may be difficulty keeping electrodes securely in place and the discomfort will increase the agitation.

Non-invasive pacing is used on a temporary basis until the patient is stabilized and either an adequate intrinsic rhythm has returned or a transvenous pacemaker is inserted, whether temporary or permanent.

1. Field JM (Ed). Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support Provider Manual. American Heart Association, 2006.2. 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122(suppl 3):S640-S656.

3. Del Monte L. Noninvasive Pacing – What You Should Know. Redmond, WA: Medtronic Emergency Response Systems, 2006.

4. Luck JC, Davis D. Termination of sustained tachycardia by external noninvasive pacing. PACE. 1987;10:1125-1129.8.

5. 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122(suppl 3):S640-S656.