Evaluating Resuscitation Quality

The goal of a hospital’s resuscitation program is to have in place processes of care to respond to medical emergencies in a timely, effective manner that leads to good patient outcomes. Elements of resuscitation care in a hospital are:

- Policies, procedures, processes, and protocols that govern the provision of resuscitation services.

- Resuscitation equipment strategically located that is appropriate to the patient population (e.g., adult, pediatric, neonatal).

- Appropriate staff who are trained and competent to recognize the patient in hemodynamic distress and to deliver emergency care.

Concurrent Evaluation of Individual Codes

We already know from Abella’s study of CPR at the University of Chicago Hospitals that:1

- Chest compression rate was too slow

- Chest compression depth was too shallow

- Ventilation rate was too high

- Time without compressions was too frequent and too prolonged

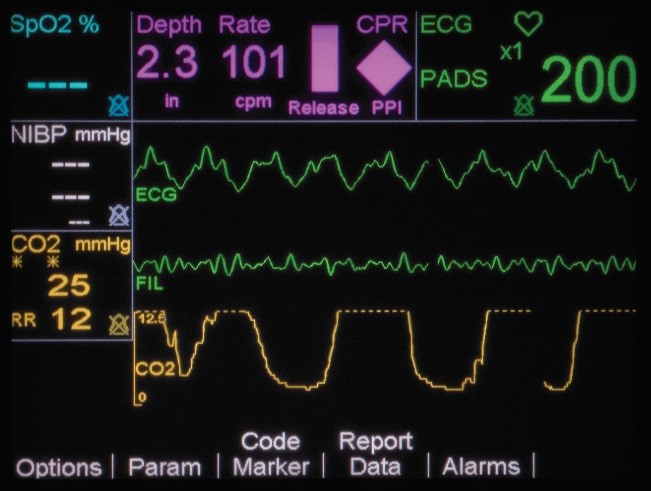

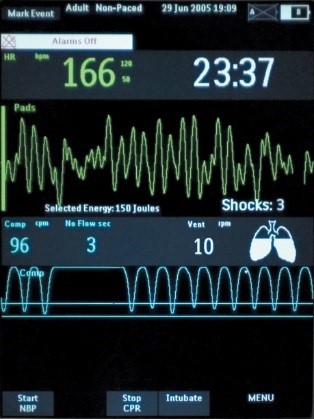

So how can the quality of CPR be evaluated during actual resuscitations and feedback be provided to the responders in order to improve upon their CPR technique? This is a critical issue given that there may be a direct relationship between quality of CPR delivered and victim survival. It can be the responsibility of the leader of the CPR team to monitor CPR performance, since maintaining standards of performance and coaching are within his/her expected role. It is important that the designated leader participate in a “hands-off” manner during the resuscitation so that s/he can monitor the larger scene and guide the team. End-tidal CO2 values have been recommended to help evaluate the quality of CPR since it correlates with cardiac output, coronary perfusion pressure, and successful resuscitation.

Other care providers who are known to carry a CPR team pager and respond to codes in order to evaluate the quality of care are the cardiac clinical nurse specialist, an Emergency Department physician, a critical care physician, RT, and the chairperson or a member of the CPR Committee. Critical incident debriefing may immediately follow codes so the players can discuss what went well and what could have gone better.

If CPR is stopped for more than 3 seconds, the idle timer shows on the display screen, prompting clinicians to resume compressions as soon as possible. There is also a Release Bar that indicates if the provider is allowing for full recoil off the chest wall. The goal is to have the Release Bar full of color. A Perfusion Performance Indicator™ (PPI) on the screen provides a visual indicator of CPR effectiveness. The PPI takes about 20-25 good quality compressions to become completely full, but empties rapidly when compressions fall below target zones. The CPR technology is FDA cleared to be used in children under 8 years of age (55 pounds/25kg or less).

Retrospective Review of Individual Codes

Documentation at codes should be completed according to the American Heart Association Recommended Guidelines for Reviewing, Reporting, and Conducting Research on In-hospital Resuscitation: The "Utstein Style." (See Documentation at a Code for more information.) The original copy of the CPR record should be placed in the patient’s medical record and a copy sent to the CPR committee for quality review.

Most institutions have a specified means for the CPR team to provide written feedback at the conclusion of a code on the process of care. All quality feedback should be set up so that it is not placed in the medical record, but rather is written on a form that gets returned in a secure manner to the designated review group, and is thus protected from legal discovery according to state quality assurance statutes.

Data from 2 in-hospital before-after studies have shown improved outcomes with a data-driven, performance-focused debriefing program. These studies used defibrillator transcripts that involved objective compression data. The 2015 AHA Guidelines state that it is reasonable for in-hospital systems to implement these types of debriefing with staff after cardiac arrest for both adult and pediatric patients.

A quality review form may be designed by a hospital with process-of-care category headings and check boxes to help the CPR team identify potential problems.

For example, categories may include:

| • Notification/paging | • Medications |

| • Arrival of team | • Vascular access |

| • Airway management | • Equipment |

| • Chest compressions | • Team function |

| • Defibrillation | • Safety/precautions |

| • Protocols: ACLS/PALS/NRP, institutional | • Documentation |

For institutions that subscribe to the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation, Resuscitation Review – Quality Management template can be downloaded to use when creating one’s own institutional form.

Each institution should decide what group(s) will retrospectively review the CPR records and quality reports from codes. Factors that should be evaluated from the CPR record are:

- Were the ACLS/PALS/NRP algorithms followed for the process of care during the resuscitation?

- Were the Gold Standard Process Variables established by the American Heart Association met?

- Time from collapse to initiation of compressions was less than1 minute

- Time from collapse to first shock when the victim is in VF/pulseless VT was less than 3 minutes

- Time from collapse to first dose of epinephrine was less than 5 minutes

- An invasive airway was placed when needed, and its location verified

- Was the documentation on the CPR record sufficient to meet institutional standards?

- Are the CPR team members current in required emergency certifications, i.e., BLS, ACLS, PALS, NRP

Written feedback should be sent in a timely manner to those participating in the code, both initial responders and advanced care responders, so that praise can be delivered for care well given and instructive feedback can be provided to improve performance in the future. It is important to close the loop of the QA process by providing the action plan for following up reported quality problems.

Evaluation of Aggregate Codes

CPR data must be analyzed in the aggregate so that the hospital understands if it is responding to medical emergencies in a timely, effective manner. Several documents define the aggregate resuscitation reports that should be generated and analyzed:

- American Heart Association Recommended Guidelines for Reviewing, Reporting, and Conducting Research on In-Hospital Resuscitation: The In-Hospital "Utstein Style" (1997)

- American Heart Association Cardiac Arrest and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Outcome Reports: Update and Simplification of the Utstein Templates for Resuscitation Registries (2004)

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations Hospital Accreditation Standards 2007

It is recommended that patient, event (process), and outcome variables be tracked for all resuscitations, displayed in a meaningful way, and analyzed to guide quality improvement efforts. Patient variables include; age, gender, witness status, location of event, date/time of event, comorbid conditions, etc. Event variables include; initial rhythm, essential interventions, event times and intervals. Outcome variables include; return of spontaneous circulation (for at least 20 minutes), discharge alive from the hospital, neurologic status at admission and discharge and length of stay. If a hospital is implementing a Rapid Response Team (RRT), then the rate of resuscitations per 1000 discharges should be calculated, so that it can be determined if the new RRT decreases the rate of resuscitations.

It is impossible to collate and display all this resuscitation data without the help of a specially designed computer software program, either developed by the specific institution or purchased from a vendor. The National Registry of CPR (NRCPR) provides a service whereby resuscitation data can be entered by the hospital into its international database and submitted electronically, with reports being received quarterly and annually in accordance with the American Heart Association “Utstein” templates. In these reports information from the individual hospital is compared with aggregate data from the participating hospitals.

Trends in quality issues should be tracked by hospitals, analyzed, and action plans made to implement small tests of change in their systems of care. Once these small changes are evaluated as an improvement, then they can be incorporated into the ongoing standard of care and educational programs for the institution.

1. Abella, et al. Quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation during in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2005;293:305-310.